Tombstone History

Ed Schieffelin directly caused the foundation of the town of Tombstone. The town itself was more of an afterthought; Ed was after valuable minerals.

Ed Schieffelin directly caused the foundation of the town of Tombstone. The town itself was more of an afterthought; Ed was after valuable minerals.

In Southern Arizona, there was a huge amount of minerals, and men combed the landscape, searching for veins of silver, gold or copper. Men who could find and exploit such mines could end up wealthy beyond belief. In today’s dollars, billions of dollars could be found. For such fortunes, some men would risk everything. Ed was one of those men.

Ed Schieffelin was born in Pennsylvania in 1847. The family settled in Oregon territory, and Ed began hunting gold and silver in 1865, first looking in Idaho, then moving through Nevada, California and New Mexico.

He was intent on making his fortune and in 1877 he was in Arizona Territory. He seemed crazed: his hair hung below his shoulders, and his beard was so unkempt that snarls and knots had formed. His clothes were shreds stitched together from whatever he had on hand: flannel, deerskin or corduroy. He was working as an Indian Scout for the Army and investigating on his own when he could. On his own time, Schieffelin would steal off from Camp (now Fort) Huachuca and scout out Apache Territory.

It was extremely dangerous. The previous year, Schiefflin and his party had been attacked by Apaches, killing a man. Schieffelin’s friends told him that if he went hunting in Apache Territory, where he would creep to within a dozen miles of the Chiricahua encampment, commanded by the legendary warriors Geronimo and Cochise, the only thing he would find would be his tombstone.

Ed soldiered on. Northern Arizona had yielded silver, but Southern Arizona was still too “hot” for geologists and surveyors to determine if or how much silver there was there. This kept most away; it did not deter Schieffelin.

Ed searched gullies and washes. His theory was that the torrential rains that poured through every summer would wash silver flakes downstream. Bear in mind that Arizona, then as now, has almost no ground cover in parts. A man can be spotted from miles away fairly easily. It would be very hard for Ed to hide his activities from a Chiricahua band. And if spotted, there would be little he could do except die, fairly miserably.

After months, Schieffelin found some silver in a wash on Goose Flats. He traced it back to its source: a thick vein of silver. It was, he estimated, fifty feet long and 12 inches wide; a fortune of silver! Ed was excited, as anyone would be. He was broke, unfortunately, and could not pay for the claim to be assayed. He threw in with a local, William Griffin, who paid for the paperwork in return for a claim of his own.

However, there was not an assay office in Tucson and the claim could be certified. Scieffelin worked for 2 weeks on another mine to get the money to find his brother, who was working at McCracken’s mine in Signal City, AZ. But when he found his brother and showed him his specimens, 20 to 30 people called them all but worthless – more lead than silver. Ed threw most of his samples away, keeping only three.

After working for a month as a common laborer, Schieffelin met the new assayer for the McCracken mine.

Ed asked if his find was worth anything. After examining them for 3 days, the assayer said the find was worth at least $2,000 a ton. Ed, his brother Al and the assayer, Richard Gird, made a gentleman agreement to split the claim. It was spring, 1878. 15 months later, Ed rode into Tucson with nearly $500,000 in silver (in today’s dollars).

Schieffelin, his brother, and Gird were running multiple mining claims: the Lucky Cuss, the Tough Nut, and the Contention. The mines were incredibly profitable and soon men arrived by the throngs, ready to work claims or to try to find their own. A town was needed to take care of all the men working these and other claims. In March 1879, Solon Allis first laid out the town and Tombstone was born.

Eventually and despite the riches (Ed’s claims were worth billions in today’s dollars), Ed headed back to Oregon to scout for gold. In May 1897, Schieffelin was found dead, slumped over his work table, checking the purity of gold samples. The ore was later assayed at $2,000 a ton. His final diary entry simply reads: “Struck it rich again, by God.” He was, per his will, buried nearby Goose Flats, where he made his first claim. He found his tombstone there, yes, but quite a bit besides.

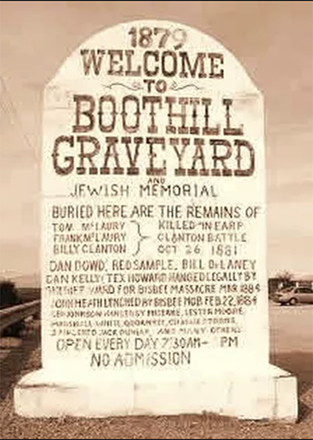

People realize, of course, that life in the 19th century was hard; how could it not be? They didn’t have wifi or GPS, after all. But it is one thing to be aware of a fact and another thing to be confronted with the messiness of reality.

People realize, of course, that life in the 19th century was hard; how could it not be? They didn’t have wifi or GPS, after all. But it is one thing to be aware of a fact and another thing to be confronted with the messiness of reality.

Elizabeth Clifton lived one of those lives, messy with the vagaries of reality and in its own way, her life was just as heroic as any gun-slinging man. She endured poverty, death, more death and Indian capture and through it all, she maintained an optimism that could read as defiance.

Elizabeth was born in Alabama in 1825. When she was 16 she married Alexander Carter, a free black man.

Thus she became Elizabeth Carter. She had no education and was illiterate. She had two children with her husband and then the family moved to Fort Belknap, Texas. Elizabeth began running the ranch that they established, while her husband and his father ran a cargo hauling business.

Elizabeth was epileptic, which did not stop her from starting another business: a boarding house.

However, in 1857, her husband and father in law were murdered. The next year she married an Army lieutenant, becoming Elizabeth Sprague. Eight months later, however, she was again widowed. She married a ranch hand a few years later, becoming Elizabeth Fitzpatrick until his seemingly inevitable murder 18 months later in 1862.

In 1864, Elizabeth and her family were the victims of a Comanche raid. Elizabeth’s daughter was murdered and scalped. Elizabeth’s granddaughter, an infant, was also killed. Not long after their capture, Elizabeth’s 13-year-old son was killed. The Indians moved north with their ill-gotten band.

Eventually, they wound up camped on the Arkansas River, in northeastern Kansas. Early in 1865, one of her granddaughters froze to death, along with a number of other children. Finally, at the end of 1865, she was rescued by General Leavenworth (of eventual Fort Leavenworth fame).

Elizabeth began caring for other kidnap victims, spending 10 months doing just that in Kansas. She was an advocate as well, demanding better care and transportation for released hostages. At the end of summer, 1866, she finally took the return journey home to Montana.

Three years later she married again, becoming Elizabeth Clifton. She moved to Fort Griffin, Texas, where she remained until her death at 57 in 1882. Yes, she outlived her husband, Isaiah Clifton, thus becoming a widow four times over.

During a hard time, Elizabeth Clifton lived an especially hard life. But she persevered and did not allow circumstances to bring her down. Her granddaughter, found frozen in the snow of a Comanche camp, was thought to be alive by Elizabeth even to the end of her life. She never surrendered the hope, the determination, that her granddaughter Milly had somehow survived.

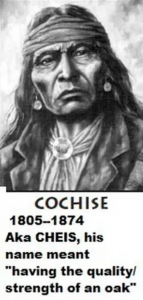

Cochise was an Apache chief, but more than that, he was the last chief to retire undefeated.

Cochise was an Apache chief, but more than that, he was the last chief to retire undefeated.

The Floyd Mayweather of the Wild West, as it were. He made peace on his terms and died naturally on his land, not land set aside for him by the United States. He was big; he stood about 6 feet tall, which was even bigger then than it is now. He stood 5 to 7 inches taller than the average Apache.

He was one of three great chiefs of the Apache, with the other two being Mangas Coloradas and, of course, Geronimo. He was buried in secret in the Dragoon Mountains south-east of Tucson, on his land, in an area known as Cochise Stronghold, so that he could forevermore keep watch over Apache land.

Cochise is believed to have been born in 1804, in the Chiricahua lands then under control by the Spaniards.

Their area ranged from Sonora, Mexico into New Mexico and Arizona. Spain tried to keep the Chiricahua in line by giving them liquor and guns and leaving them alone. When Mexico took over, however, all that changed.

The Mexicans gave nothing to the Apaches, who resorted to raids to get what the Spaniards used to give. As a young man, Cochise would have taken part in these raids, which were viewed with alarm by the Mexican government.

Their reaction was swift, sharp and brutal: they began killing every Apache in sight, whether a warrior or civilian. The Mexican army was aided by American and Native American mercenaries, who crossed the border into then-Mexico, hunting for scalps.

Cochise’s father was killed in one of the retaliatory strikes, which deepened his hatred of Mexicans. He hated them for good reason, for as brutal as Americans were, the Mexicans were even more savage. In 1848, Cochise was captured by the Mexican army, but being a valuable captive, he was not harmed. He was traded for a dozen Mexican soldiers.

The United States acquired the Chiricahua Apache lands after the war with Mexico ended and at first everything was fine between the two nations, mostly because there was no reason to try and force the Chiricahua off their territory.

In 1861 that began to change when Cochise was accused of a kidnapping raid likely carried out by Coyotero Apache. A Lt. Bascom tried to arrest Cochise on the matter, but Cochise fought his way out and escaped. Bascom took hostages, Cochise’s relatives to use as leverage.

Cochise took hostages of his own, his fury rising like his impatience. Negotiations broke down with the arrival of Army reinforcements and both sides ended up killing their hostages. Cochise’s brother and two nephews were among those killed and Cochise declared war on the United States.

Cochise’s war would last 11 years and result in hundreds, possibly thousands of dead Mexicans and Americans.

The U.S. was distracted by the Civil War and Cochise, aided by his father in law, Mangas Coloradas, conducted countless raids throughout their territory. Coloradas, duped by a false flag of truce, was captured and killed in 1863. Determined, Cochise continued his revenge.

In 1872, the United States sued for peace and signed a treaty with Cochise. Even in old age, possibly 67 or 68, Cochise was a fearsome presence: back straight and clear-eyed. The war ended. Cochise retired to his lands, dying, possibly of abdominal cancer, in 1874.

He was buried in the Dragoon Mountains, overlooking the lands of the Chiricahua. The general area is known as Cochise Stronghold. The specific place of the burial was known only to Cochise’s loyal men and Tom Jeffords, his only white friend (and who helped negotiate the peace treaty). When those few died themselves, the location of Cochise’s final resting place passed into the wind.

Cochise is remembered for his strength and implacability, his refusal to surrender to inevitability. He has come to be respected for his stand against the encroachment of the United States.

Cochise County, Arizona was named after him; it was the middle of Chiricahuan land in Arizona, encompassing the town of Tombstone, Arizona as well. He was a complex man: compassionate to his people, yet unspeakably cruel to enemies, honest enough to admit thievery and warm and personable when met in camp.

Cochise was a strong leader at a time of unprecedented pressure upon the Apaches, a time when the United States arrived to stake the claim it had won from Mexico and Cochise held them off. 2 years later, in 1876, the United States closed the Chiricahua Reservation; silver was in the area, and it needed mining. The Chiricahua went back to war, but 10 years later they lost and were ultimately resettled in Eastern New Mexico. It is not on Chiricahuan land.

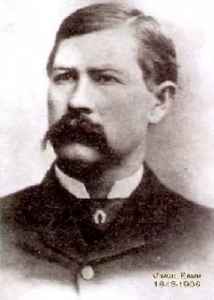

Virgil had the misfortune of being overshadowed by his much flashier younger brother. You know the one I mean. For all of the shenanigans, he found himself involved with, Virgil managed to make it to a relatively old age (although not as old as that flashier other brother). Before his legendary stint as a lawman, Earp served in the Civil War on the Union side. After his death, did he come back to the site of his greatest moment?

Virgil had the misfortune of being overshadowed by his much flashier younger brother. You know the one I mean. For all of the shenanigans, he found himself involved with, Virgil managed to make it to a relatively old age (although not as old as that flashier other brother). Before his legendary stint as a lawman, Earp served in the Civil War on the Union side. After his death, did he come back to the site of his greatest moment?

Virgil was born in Kentucky in 1843 and served with the Illinois Militia in the War. He spent his time on garrison duty in Tennessee, bored from a lack of action. Unlike his brother James, who was severely wounded, Virgil made it to the end of the war unscathed.

Prior to the war, Earp had married an Ellen Rysdam, but a false report of his death led to her marrying another. Coming home to find her gone, Virgil took to the road and migrated to California. After wandering east to Dodge City, Virgil came to Arizona Territory in 1877 and moved to Tombstone at the end of 1879. He was appointed as a Deputy U.S. Marshal and then, after Fred White was killed, became the second town marshal of Tombstone.

After some run-ins with the Cowboys, the Earps and Doc Holliday met the Clantons at the O.K. Corral and had themselves a gunfight in October 1881. Two months later, unidentified men ambushed Virgil as he passed the Crystal Palace. 19 bullets were fired, four striking Virgil. He had four inches of bone removed from his right arm, permanently crippling him.

After a couple of years recuperating in California got involved in another famous dustup, the “battle of the crossing” working for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1905 he contracted pneumonia and died after a six-month battle.

Since his passing, Virgil has been seen stepping off the sidewalk near the Crystal Palace, but the figure never makes it to the other side. It seems to be a residual haunting, a remnant of the intense suffering Earp suffered in his assassination attempt.

This photo, from Clantongang.com, shows furious activity in the area of the Crystal Palace, where Virgil was struck.